Breathe

Open

Skin

touch

Expand

Accumulate

Ripple

Break

Release

collapse

skin

multiply

Grief

Grief

Skin

Specimen

Collective grief

Collapse

Escape

Allow

Hold

Liquidity

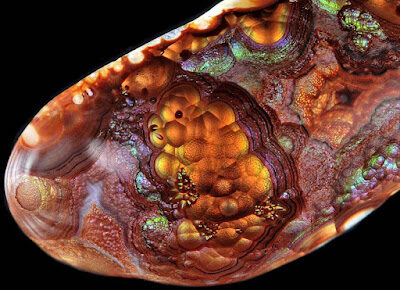

Globules

No more time for Iridescence

Rock

Water

Flow

Hover

Collapse

Levitate

Crystallise

Focus on land, material and identity.

Rupture and longing. Fragments of meaning or expression, reflecting the sum of parts into a new unit. Materials reseach, working through the lens of collapse and accumulation.

Looking for narratives expressed in material properties and our relationship to them. Breaking things down into parts, encouraging constraints and random factors, deconstructing, re-assembling, using errors, rules, serendipity, and the properties and behaviour of clay, water and stone.

Interested in personal narratives as well as collective narratives told through material, found in mythology, geography, repetition and maps.

Glazes in the City

The next edition of Glazes in the City will take place in April. To reserve a spot please email me

This is a two day intensive course that covers theory and practice. The class investigates urban narratives with the aim of ‘de-exoticising’ materials and place, delving into the mechanisms of storytelling and the various threads we can pick up when incorporating materials into our artistic practice. We will discuss the ties between ceramics, land, identity and working with local materials. We will also delve into how these correlate with narratives about land, extraction and exploitation. You will learn how to collect and process materials, and you will make a series of glaze tests to take home.

The class costs 375€ inc. VAT, daily lunch and snack are included. The class is limited to eight participants.

Mentorship

I offer individual mentorship sessions for anyone with a material or ceramic practice that would like more guidance in their process.

Together we can unpack throughts around a specific project your are undertaking, we can make a plan to develop your work, or you can use the sessions as a sounding board and accompanying presence. The content is up to you and we can outline this in an introductory 15 minute session.

Sessions take place on Zoom and last 40 mins – 1 hour, you can book sessions one at a time or as a set of three, the price is 90€ for a single session or 250€ for three, inc. VAT.

To book a session please email me

contact

maiabeyrouti ( a ) gmail.com

instagram.com/maia.beyrouti

La reflexión de la materia

Reflections on my practice for infocerámica

Kindly translated into Spanish on their site by Wladimir Vivas

As I was contemplating the invitation to write about my work for Info Ceramica, I saw an opportunity to unpack some thoughts around my relationship to the ceramic material. It feels like a challenge as it is a vast yet specific connection viewable through various lenses, the lenses themselves being under observation and part of the work. Here, I would like to talk mainly about my sculptural practice.

A central part of my work are the qualities of maps and territories (Cf. Korzybski “the map is not the territory”). I think using this as an analogy to look at how I engage with material works well as I relate with my practice on different levels, like an overlay of maps at various scales through which we can zoom in and out of.

On the personal scale, there is my individual relationship to clay. Parallel to that, I can zoom out and look at the larger collective entanglement with the material. I can zoom even further and consider outer space and the rich narratives about material physics and particles that inform how we navigate the world. From that point I can also zoom back in but away from the human this time, and into the material; the mountain, the cave, the brick, the soil, which my work also concerns itself with. This parallel zooming in and out movement is also circular, from human to ceramic and back again, as the material gives birth to archetypes in our psyche, in my psyche, and informs my relationship to clay.

So as an individual, ceramic is enmeshed with my personal identity, namely my longing for reconnecting with ancestral land and people. As a diaspora Palestinian clay has been a vector for reconnecting to soil and expressing this dispossession, with clay becoming a universal proxy. The very choice of working with clay has felt for me at its core like a constant re-enactement of this longing, no matter what I make.

There is also the idea of memory and my larger cultural identity. In that sense I have used the ceramic practice to make work that fills my need to find my way back to – biological and cultural – ancestors. I look at material as a door which could give me access, even if only remotely. Whilst this was tentative or symbolic at first, I realised the very act of searching and tip-toeing around my Palestinianess was my identity – the aspect of not being able to find the way in, or to inhabit it fully, defined my experience as a diaspora Palestinian for a long time. There is a compulsion to break open the material and to have it claim me back.

In my work I also zoom further out to a ceramic-human engagement that is anchored in material. Craft is a technology of time, of memory, of our capacity to store concepts in the ceramic material. Clay has properties of lending itself. The oldest piece of ceramic on record is a scultpure of a female figure, the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, made 30,000 years ago. Whoever made it took a lump of clay and used its properties to create a portable item capable triggering thoughts, and I felt a need for engaging with this ability, to insert idea into material, and also to be able to extract it.

Using clay as storage is central in my work, both in the sense of the functional vessel, and in the abstract sense of imbuing objects with the symbolic. Using the vessel as a symbol for storage, I usually close the vessels I make with various slabs that stand on top of the opening. With these pieces I feel the close to clay and to a feeling for craft and memory. This obstruction is also an impulse to accumulate, to stack, to protect, to store for later and to remember. These are qualities I find inherent to the collective relationship to clay and that I want to be in conversations with.

Continuing to zoom out, I reach a blurrier map of archaic concepts where the material is entangled with the collective unconscious. Here I can freely engage with archetypes; the seed, the vessel, the cave, the extruded form. It feels like a forge, a primordial soup, and a place that doesn’t ask for answers. It is also here that I look at matter as a lens to view collective narratives at their source. I begin to cross a threshold where I can zoom back in through another door, moving from the human aspect to the material properties themselves.

Having changed scales from the individual to the collective to where we meet the abstract, I now start to zoom back in, into the clay matter. Like a human-to-clay gradient. And my work concerns itself very much with this because ultimately, an object takes form and this form is somewhat not up to me.

This is my main interest in materials, the place where their physicality meets the abstract. Ceramic materials offer a perfect medium for this – they lend themselves effortlessly for both metaphor and metamorphosis. Metaphor, as in the ability to engage with the human mind in an abstract realm – imagination, symbolism, belief – and metamorphosis, which is then the physical properties; malleability and capacity to change with temperature.

I wonder what narratives are present within the material that have shaped my experience. In practical terms I look for and question concepts I discover in writings about climate change, outer space, nature and mythology. Narratives we use to dehumanize, legitimise, or empower and liberate. Scripts by which we live our lives. It is important to me that this isn’t a place I enter with intentions for answers or beneficial properties.

In the studio I scale further into the matter’s properties, to the particles and their chemistry. My interest in material research is to engage with how the material behaves, and what new narratives emerge. Collecting, creating and melting glazes and materials is a way to look at how matter expresses itself, a desire for the materials to be vocal in a way I maybe don’t understand, but can recognize. I ask myself, how do I engage with the blurriness without the end goal of clarification? I orchestrate setups where I have less control, an invitation for material to be revealed, and then often reassemble the parts into a sculpture where our conversation continues.

The idea in my work is then to not expose something definitive, but to break open with the material, to play around with its propositions and wonder about what can be expressed.

As I work, all of these maps are mirrors to something singular and nebulous which is a very restful and freeing experience to me. An absence of absolutes. The pieces are a combination of these aspects and the starting point can be anywhere on the scale.

So my work deals specifically with this property of origin, whether mine, ours, or the material’s, and where those overlap. This is my connection to clay.

Berlin Rubble as a Site of Memory Culture During a Genocide.

Part I. Trip to the Brickworks

We arrive at the brickworks late morning in June and park the car by the large ring kiln, now a ruin but with the tall chimney still intact, rising above us like an ominous beacon of late 19th century industry.

As a Palestinian, it is impossible for me to ignore the threads of repression, violence and genocide woven into the topic of land and technologies. Standing in front of this massive kiln, the chimney rises like a hallmark of horrors to come.

Rubble in Berlin was never innocent but today it is a place that feels to me like a sacred symbol that is untouchable as it mirrors the devastation of Gaza, the massacre of Palestinians, and for this same reason it compels me as an urgent and loud site of intervention. The genocide is still happening. The genocide is no longer happening. The locations are different but the sites are the same.

We walk around the kiln and a man comes out of a building which appears to be a Kita. A stocky, pale, red-headed German man in his forties comes towards us with a stern face. He tells us we are not allowed here and must leave. We explain we are artists and interested in the kiln’s structure and history. He doesn’t budge, tells us it is now a storage for builders and asks us, again, to leave. We backtrack, feeling confused about his forward, defensive stance that leaves us feeling somewhat unsafe. (Is he protecting the kids? From what? Us?)

We drive a bit further up the road, I notice it is slightly convex and paved with large uneven stones. Signs warn us that unauthorized parked vehicles will be towed. We see some men working on a house and I step out of the car to ask for directions, only too aware I have the palest skin of the three of us and embarrassed to imagine it gives us an advantage. I ask them how to get to the lake and where to park, trying to push a harmless foreigner vibe as far as possible, again embarrassed to imagine this gives us an advantage. We get their authorization to park nearby and walk from there.

As we pack our rucksacks for the walk I notice Jorge dropping a geolocation pin on his phone and send it to a friend. He says that way if anything happens someone knows where to find us. It dawns on me that for him, a Puerto Rican man, walking in Brandenburg is the same felt sense of danger as for me when I go on a date; taking the same precaution when walking into unknown and not impossible danger. I understand his concern, Brandenburg is AfD territory. Already earlier he was on the lookout for the Confederate flag, which is often used as a symbol of right wing stances here where Nazi symbols like the black cross are illegal.

We are here because Amara is doing an artist residency at Savvy Contemporary and has invited me to join her in an open conversation about land and identity. We decide to go and collect some local clay to work with and Jorge joins us for the ride. During our first meeting we had a discussion around words and objects, and I expressed the inadequacy and limitations of each to really express the thoughts and emotions and ideas we want to convey. We agree on a certain frustration and also that it’s perhaps too much pressure anyways to put on a single object. This suddenly seems to open up and multiply possibilities rather than limit them. We talk about what it is to work with material regarding our respective identities as a Palestinian and a Puerto Rican, our relationship to land, ancestry, culture and the hypocrisy and theft of colonizers.

After our meeting, an anger that is present in me finds a direction, or perhaps the inadequacy of objects reminds me I am after questions not answers, and I find a bit of courage to finally enter the world of clay and bricks in Berlin, which has been difficult for me up till now, knowing it will awaken so many parallels. Working with clay is working with archetypes, with symbols and with memory – how can I approach clay in Berlin as a Palestinian and not address Berlin’s history, its destruction, its walls, its relationship to genocide?! The insanity of Berlin becoming actual twin cities with Tel Aviv. How will I deal with bricks and rubble, with kilns, with the current identity of the land itself when the clay used for Berlin’s bricks is found in the depths of Brandenburg, which is now politically extreme right territory?

On the drive there Amara reminds me of clay’s innocence, but also of its largeness.

She asks me if I intend to address or incorporate this somehow into the work. After all, this clay took hundreds of thousands of years to become, how do I feel about addressing it as a symbol of this tiny fragment of history that is the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries?

These questions give me pause for thought. I decide that it’s important for me to carry my emotional impulse and my intentions no matter how precise they are, how present and so very now, when meeting such a large material. It is where material and I overlap after all and I am by far the smaller one. I always experienced my work as a collaboration with material, and in this sense material will also bring in its own voice on its own terms. I am not trying to coerce it and there will be plenty of space and an inevitability for clay itself to address this vast timelessness. In my experience wild clay brings a mixture of a largeness that can hold it all as well as its own subjectivity. I don’t think clay is impartial. This is a strange thing to say because we can be philosophical about the idea of “will” here but I want to clarify and say clay doesn’t have a will the way we understand our own sense of will. Still I insist on using ‘will’ to talk about clay’s material qualities and the sense it imparts that it belongs to itself. I find it in how it moves in my hands and in the kiln – these can be referred to as its technical properties of course but I find it also in the way clay can express something of itself like this. We also talk of clay having a memory, and as ceramicists, some of us choose to allow for a certain behaviour of the material we don’t wish to account for. This is not for lack of scientific rigour or knowledge of the material, this is an intentional choice on the part of the artist to allow clay to express something of its own when allowed to do so freely. At the risk of anthropomorphising material I still wish to use the terms ‘will’ and ‘memory’ as phenomena that can nonetheless lay outside of human-centric experiences. It is also a wish to counterpoint ideas of scientific rigour which we too often place as above other ways of knowing and working. It is a way of meeting material that allows for a relinquishing of control, and a collaborative element emerges. Perhaps it is linked to the timelessness clay holds that there is a desire to work with it like this. We start to touch things we cannot name and clay is especially good at that, it eludes us somehow and reminds us of things bigger than ourselves, things we cannot fully grasp. It is no wonder it features in so many origin myths, not only for its corporeal or grounding qualities, or its ability to morph and be molded, but I think there is a direct experience of origin within it; billions of years ago, we crawled out of the mud. We went from the water to the land, and I believe this is deeply imprinted in our collective unconscious, our nervous systems, and in our DNA. I believe clay helps us calibrate our nervous systems.

After parking we head to the first location by a hill. Jorge has taken to being the location scout and we gladly follow his lead. We pause halfway up the hill and I pick up a rock to inspect. Large ants teem out of holes under it and climb onto my foot. Amara is alarmed, don’t they bite? They could, but I don’t expect they will.

This is the first of many instances where I am enchanted by our expectations of fauna. At some point she is stunned by a lizard, it is neon green! We are here to find clay and again I am reminded of the aliveness of this material. A little later, as we are picking up large chunks of clay from an area where tree roots overhang and are intertwined with the soil a spider comes out carrying an egg sack. The mother. This is her home and I take it as a sign to stop collecting here and move on to another site.

Later on we cross paths with a small but spectacular beaver dam. A sizeable tree nearby has been started on by some beavers and still stands, a triangular notch compromising its verticality.

There is this wonderful and quenching aspect of clay, inextricably linked to water. I think to myself, in a sense clay is a manifestation of water in mineral form.

We watch the dam, and the small lake it has created. The beauty of tree roots, now visible due to the removal of soil by water. It looks like a small mangrove. On one side, a lake, on the other, a small river. Amara points out the difference in water quality, the dam is also an impressive water filter. Jorge later posts a comment on social media with the beaver dam as a photo: “how is your key instinct to get a bunch of detritus and create a dam that can stop a river?”

I also pause when I read this. The instinct these animals have, to be a beaver, to be preoccupied with the business of felling trees and making dams. Why do they do this? Why not?

I think again about the imposed hierarchies of the maps we use for understanding and creating; poetry, the scientific method, intuition. How hierarchies have encouraged a rupture from our bodies and from systems of personal and collective knowledge. Being self-referent in knowing what you feel. Co-regulating in communities. Felt senses of meaning.

At the last State of Ceramics talk in March, one of the participants, Ryze Xu, said “Clay made me realise you can only access reality through fantasy” and I remember the calm and reassuring softening of my body when he said this. It reminded me of the ways we can be creative and playful and subjective, rather than striving for accuracy and correctness which is usually a game of pin the tail on the donkey. This phrase reminded me to keep heading in the direction of my own truth. And for this reason I prefer to share the questions that are on my mind in order to have conversations, rather than arrive at any final answer that will anyways eventually calcify before it needs to dissolve again. Still, things are also time-dependent and carry the urgency to be said in no uncertain terms, clay is a material that vitrifies, after all. Perhaps the particles of clay also carry this idea; the dissolution of stone into particles so fine they lend themselves to becoming anything you want. And maybe this is also what Ryze was alluding to, that we meet clay in reality almost like a dream-form, and we each borrow meaning and intention from the other, bringing that intention into the real as object. I believe no matter how mundane or what the function, clay objects intrinsically hold power as a source of symbol and so in this way are very telling about what it is exactly we are involved in doing.